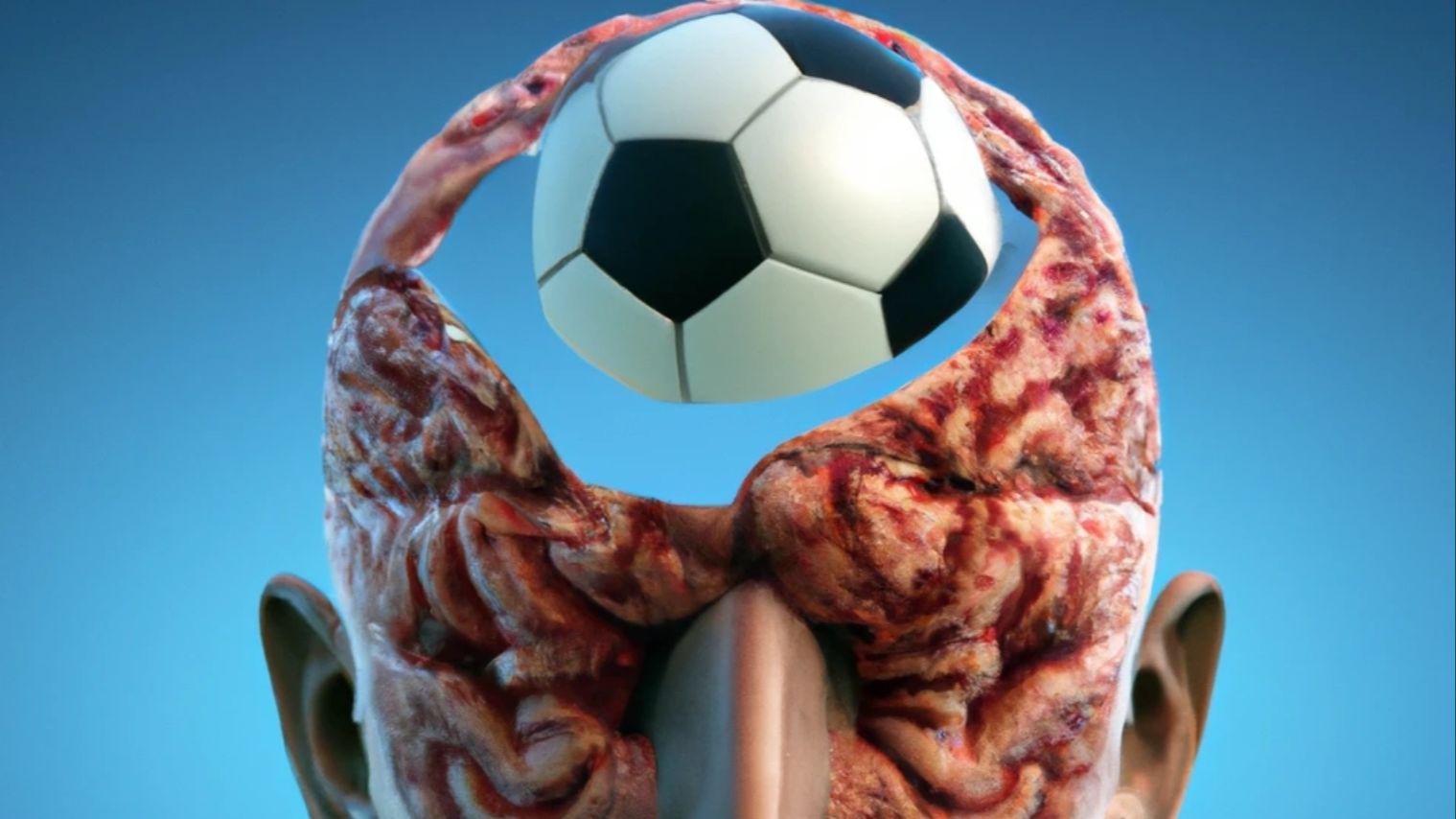

Soccer & neurodegenerative disease. Should we be worried?

Apr 20, 2023

This new study provides some interesting data about football (soccer) and neurodegenerative disease. Below is a summary and discussion of what they found.

Ueda, P., Pasternak, B., Lim, C.-E., Neovius, M., Kader, M., Forssblad, M., Ludvigsson, J. F., & Svanström, H. (2023). Neurodegenerative disease among male elite football (soccer) players in Sweden: a cohort study. The Lancet. Public Health, 8(4), e256–e265.

Football (or soccer in Australia/US) is the most popular sport in the world, with millions of people playing competitively. However, concerns have been raised about the potential increased risk of neurodegenerative diseases associated with playing football. Traumatic brain injuries, including concussions and repetitive sub-concussive injuries without symptoms, have been previously linked to an increased risk of neurodegenerative diseases, potentially through a specific neurodegenerative pathology known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (1). While symptomatic brain injuries are infrequent in football compared with other contact sports, the trauma sustained through repeatedly heading a football has been suggested to cause neurodegeneration, although the evidence for such a link is inconsistent, incomplete, and controversial. Studies have shown that former professional male football players have a higher risk of death with neurodegenerative diseases compared to the general population, including Alzheimer's disease, other types of dementias, motor neuron disease, and Parkinson's disease. This has led to updated guidelines to reduce exposure to heading among youth players and limits for headers involving higher forces for adult amateur and professional players in England. This study aimed to assess the risk of neurodegenerative disease among male football players in the Swedish top division compared to matched controls from the general population.

This cohort study included all male football players who had played at least one game in the Swedish top division Allsvenskan, from Aug 1, 1924 to Dec 31, 2019. Each football player was matched with male controls from the general population, in a 1:10 ratio, to form a base cohort. The matching was done based on year of birth, region of residence, and vital status. The primary outcome was neurodegenerative disease, a composite of Alzheimer's disease or other dementias, motor neuron disease (including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), and Parkinson's disease. Secondary outcomes were each type of neurodegenerative disease, as well as death with the neurodegenerative disease composite and with each of the neurodegenerative disease types. Data sources included the Total Population Register, National Patient Register, Cause of Death Register, and National Prescribed Drug Register.

Results showed that professional football players have a higher risk of developing neurodegenerative disease compared to those who do not play the sport professionally. The study included 6,007 football players and 56,168 matched controls, and the risk of neurodegenerative disease was 1.46 times higher among the players than controls. However, the risk of Parkinson’s disease was lower among football players than controls. Interestingly, outfield players had a higher risk of neurodegenerative disease than goalkeepers. The study did not find a significant increase in the risk of motor neuron disease for football players compared to controls. The study highlights the need for ongoing research to further understand the risk factors associated with neurodegenerative disease among professional football players.

What does this mean? Male football players in the Swedish top division had a 1.5-fold increased risk of neurodegenerative disease compared with population controls matched on sex, age, and region of residence. The risk increase was observed for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, while the risk of motor neuron disease was similar among football players and controls, and the risk of Parkinson's disease was lower among football players compared with controls. The risk increase for neurodegenerative disease was only observed for outfield players and not for goalkeepers. The study suggests that the weaker association with neurodegenerative disease observed for football players in Sweden compared to Scotland (2) (3.5-fold increase in neurodegenerative disease) could reflect differences in playstyles, practice routines, and frequency of play that the players were exposed to. The study also reminds us that the higher risk of neurodegenerative disease observed among football players may not just be football related and could also be explained by exposures other than trauma to the head. Known risk factors for dementia include air pollution, less education, infrequent social contact, excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, hearing impairment, depression, head injury, physical inactivity, and cardiometabolic risk factors (including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity). In the study, football players had a slightly lower risk of all-cause mortality, death without neurodegenerative disease, and death with chronic obstructive lung disease or lung cancer, while there was no significant difference between the groups in the risk of death with cardiovascular disease and death with alcohol-related disorders. The study also found that professional football players in Scotland had a lower risk of all-cause death, death from ischemic heart disease, death from lung cancer, and suicide than population controls.

This study reaffirms that sport has some risks and benefits when it comes to long term health. The 1.5-fold increase in Alzheimer’s and some other dementias warrants further research. Currently we are improving the way we assess and manage concussion in sport through better multimodal baseline/post-injury assessments and management of persistent symptoms. Perhaps we should be assessing and tracking the brain health of football (soccer) players to help identify any issues that may accumulate from repeated sub-concussive impacts from heading the ball? I have had the privilege of meeting and treating ex professional football players in their 60s and 70s. They are quick to remind me that heading the old-style leather balls was very different, especially when it was heavy, wet and muddy! New synthetic balls and better pitches may already be helping?

Anyway, its all food for thought.

James.

- McKee, A. C., Stein, T. D., Huber, B. R., Crary, J. F., Bieniek, K., Dickson, D., Alvarez, V. E., Cherry, J. D., Farrell, K., Butler, M., Uretsky, M., Abdolmohammadi, B., Alosco, M. L., Tripodis, Y., Mez, J., & Daneshvar, D. H. (2023). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE): criteria for neuropathological diagnosis and relationship to repetitive head impacts. Acta Neuropathologica, 145(4), 371–394.

- Mackay DF, Russell ER, Stewart K, MacLean JA, Pell JP, Stewart W. Neurodegenerative disease mortality among former professional soccer players. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1801–08.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.